Phorusrhacos: The South American Terror Bird

Introduction

Phorusrhacos, commonly known as the “terror bird,” was one of the most fearsome predators of the Cenozoic Era. This flightless bird lived during the Miocene epoch, approximately 20 to 15 million years ago, in what is now South America. With its powerful legs, massive beak, and predatory instincts, Phorusrhacos was a top predator in its ecosystem, striking terror into the hearts of smaller animals that shared its environment.

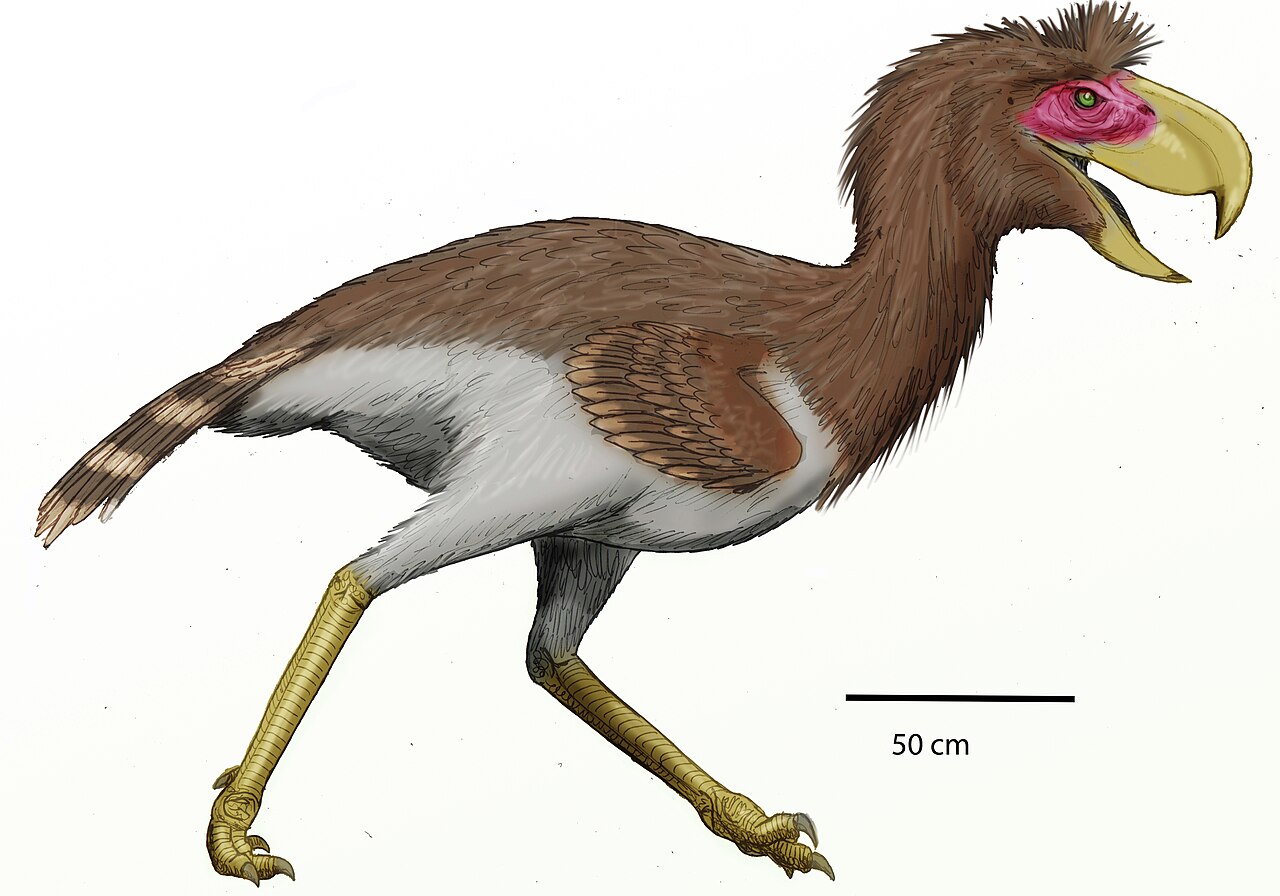

Physical Characteristics

Phorusrhacos belonged to a group of birds known as Phorusrhacidae, or terror birds, which were characterized by their large size, powerful build, and predatory nature. Phorusrhacos stood about 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) tall and weighed around 130 kilograms (287 pounds). Unlike modern birds, it was flightless, with reduced wings that were likely used for balance and perhaps intimidation rather than flight.

The most striking feature of Phorusrhacos was its enormous, hooked beak, which could reach lengths of up to 60 centimeters (24 inches). This beak was a formidable weapon, capable of delivering lethal strikes to prey. Its strong legs, equipped with sharp claws, made it a fast and agile runner, able to chase down and overpower its prey.

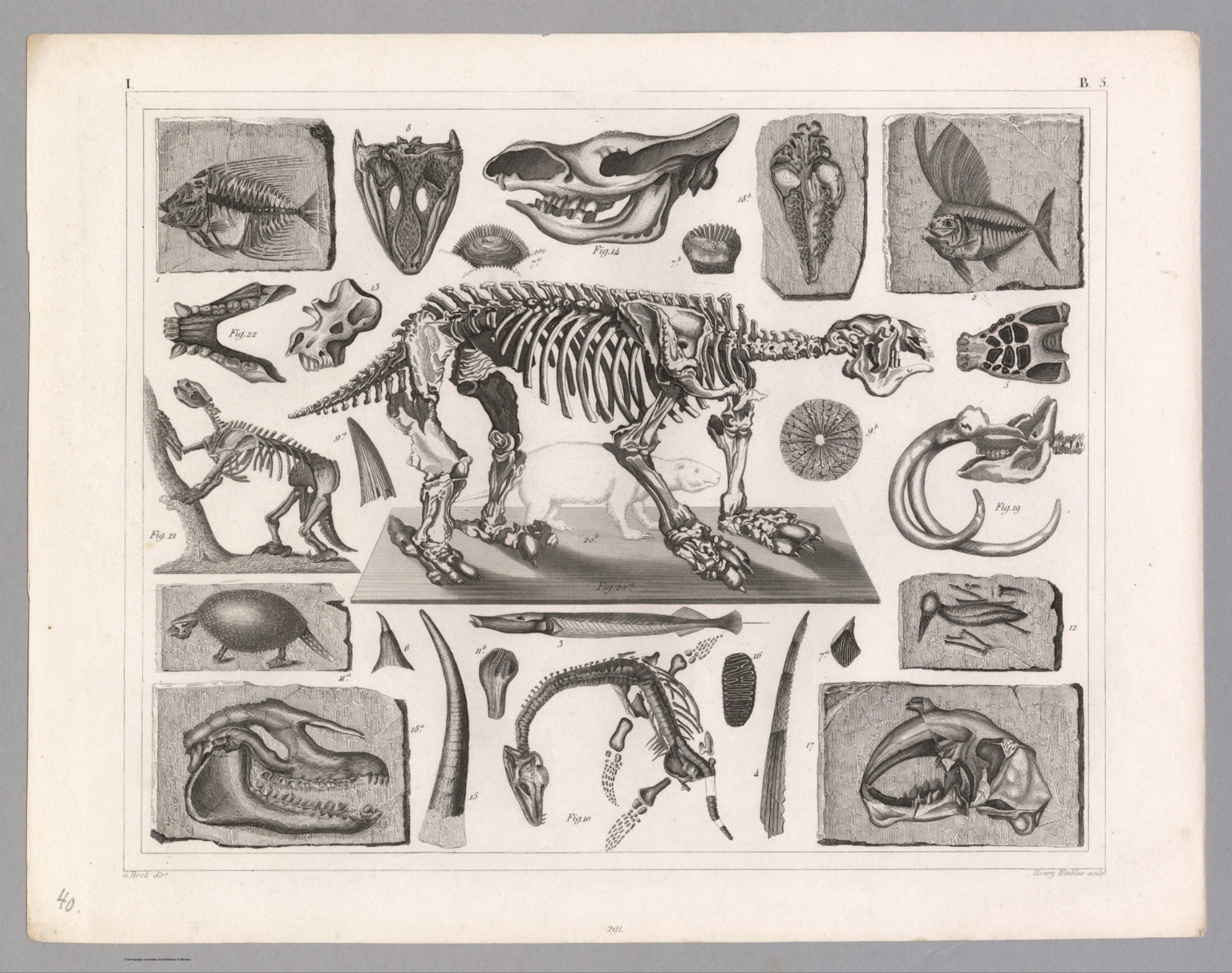

Skeletal cast mounts of Yangchuanosaurus and Tuojiangosaurus on display at the Beijing Museum of Natural History. Photo by Jonathan Chen

Natural History and Discovery

The first fossils of Phorusrhacos were discovered in the late 19th century in Argentina, specifically in the Santa Cruz Formation, a site rich in Miocene fossils. The discovery of these fossils was significant, as it provided the first evidence of large, flightless predatory birds in South America. Since then, additional fossils have been found, allowing paleontologists to reconstruct the anatomy and behavior of this fearsome bird.

Phorusrhacos is one of the best-known members of the Phorusrhacidae family, a group that once included several genera of large, predatory birds. These birds thrived in South America, which was an isolated continent during much of the Cenozoic, leading to the evolution of unique and diverse fauna.

Biosphere and Habitat

During the Miocene epoch, South America was an isolated landmass with a wide range of environments, from tropical rainforests to open savannas and arid deserts. Phorusrhacos likely inhabited open grasslands and wooded areas, where its ability to run swiftly would have been an advantage in hunting.

The climate during this period was warmer and more humid than today, with significant climatic fluctuations that shaped the vegetation and animal life. The isolation of South America allowed for the evolution of unique species, many of which were not found anywhere else in the world. Phorusrhacos, as a top predator, played a crucial role in maintaining the balance of its ecosystem.

Skeletal cast mounts of Yangchuanosaurus and Tuojiangosaurus on display at the Beijing Museum of Natural History. Photo by Jonathan Chen

Diet and Hunting Behavior

Phorusrhacos was a carnivore, preying on a variety of smaller animals that shared its environment. Its diet likely included small to medium-sized mammals, reptiles, and possibly other birds. The bird’s large beak, with its sharp, hooked tip, was ideal for seizing and delivering powerful blows to its prey, likely causing fatal injuries with a single strike.

Paleontologists believe that Phorusrhacos was an active hunter, using its speed and agility to chase down prey. Once it caught its prey, it would have used its beak to deliver crushing blows or to tear apart flesh. Its strong legs and claws may have also been used to pin down struggling prey. The hunting strategy of Phorusrhacos likely involved ambush tactics, taking advantage of its environment to surprise and overpower its victims.

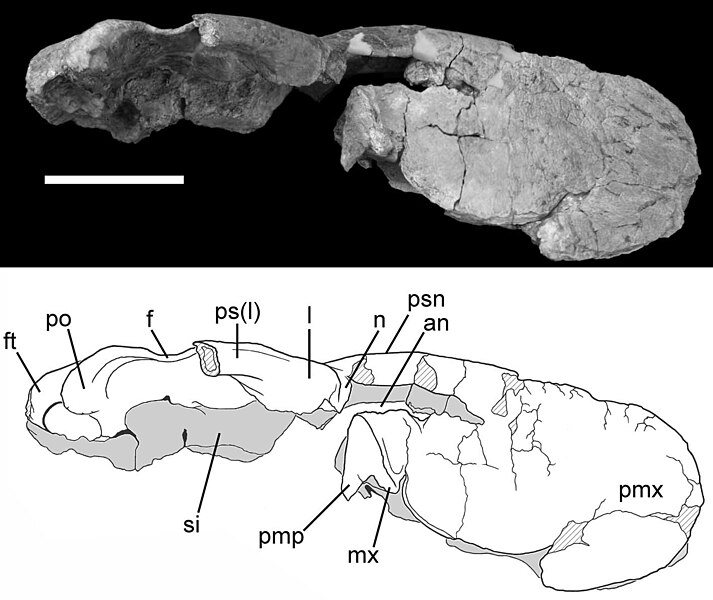

Phorusrhacos longissimus holotype mandible by Federico J. Degrange, Drew Eddy, Pablo Puerta, and Julia Clarke.

Coexistence with Other Animals

Phorusrhacos shared its environment with a diverse array of animals, many of which were unique to South America due to the continent’s prolonged isolation. Some of the animals that coexisted with Phorusrhacos included:

- Notoungulates: An extinct group of hoofed mammals that were common in South America during the Miocene. These herbivores ranged in size from small, rabbit-like creatures to larger, tapir-like animals and were likely primary prey for Phorusrhacos.

- Glyptodonts: Large, armored mammals related to modern armadillos. Although heavily protected by their bony armor, young or small glyptodonts may have fallen prey to Phorusrhacos.

- Marsupials: South America was home to a variety of marsupials during the Miocene, including opossum-like creatures and other more specialized forms. Some of these marsupials might have been on the menu for Phorusrhacos.

- Xenarthrans: This group includes creatures like giant ground sloths and anteaters. While the larger members of this group were likely too big for Phorusrhacos to tackle, smaller species might have been preyed upon.

The presence of Phorusrhacos as an apex predator would have exerted significant pressure on these species, influencing their behavior, habitat use, and evolution.

Conclusion

Phorusrhacos is one of the most iconic examples of the “terror birds” that once roamed South America. As a top predator, it played a vital role in the ecosystems of the Miocene epoch, preying on a variety of animals and maintaining the balance of species in its environment. The study of Phorusrhacos and its relatives provides valuable insights into the unique evolutionary pathways that developed in isolated South America during the Cenozoic Era. Today, Phorusrhacos remains a symbol of the fascinating and sometimes terrifying diversity of prehistoric life.

Featured image credit:

Phorusrhacos longissimus 2D illustration by ДиБгд.

Editor’s Note:

I use Open AI’s Chat GPT to write Species Profiles. Read more about this and get a copy of the prompt I’ve created here.

editor's pick

latest video

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua